|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

A Great Ball in 1897

"At the Duchess of Devonshire's historic ball at Devonshire House last week, a photographic studio formed part of the arrangements, and we read that a camera was much in request to record some of the wonderfully accurate costumes worn by the guests. These included the creme de la creme of Society, from Royalty downwards, and some of the most celebrated men and women of history were personified. A photographic record of the scene and those who took part in it was no doubt secured, and in future times, when the doings of this great year are calmly narrated in calm prose, its interest will be extremely deep."

Photographic News, 9 July 1897

|

|

|

|

|

Devonshire House, built 1735-7 by William Kent for the 3rd Duke of Devonshire, was situated on Piccadilly, one of London's most fashionable sites with a view down across Green Park to Buckingham Palace and with a huge landscaped garden behind which stretched all the way up to the current Berkeley Square.

The exterior was of plain unclad brickwork and it was shielded from the street by a high brick wall, giving passers-by the impression that it was "cheerless and unsocial by day, and terrible by night..." However, the exterior hid some of the most imposing interiors of any of London's grand houses and its collection of paintings was much praised.

|

Devonshire House, Piccadilly, c 1895.

At street level, almost none of the house could be seen, screened as it was from pedestrians by the high brick wall and plain wooden gateway. The historian JH Jesse was rather scathing about the merits of the mansion: "except during the brief period when the beautiful Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, held her court within its walls...little interest attaches to the present edifice."

|

Louisa, Duchess of Devonshire (1832-1911) was one of London's foremost political hostesses, and as such, when word got around that she was planning a costume ball to celebrate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee on 2 July 1897, there was no attempt by other London hostesses to hold a competing event. Instead, they invested all their efforts into ensuring that they were on the guest list. As the respected mother of the nation, Queen Victoria's sixtieth anniversary on the throne along with her recently acquired extra title as Empress of India, her jubilee was celebrated, in the press at least, with a feeling of exhilaration and respect tinged with hysteria. By this time of her life, Queen Victoria had been a black-clad and gloomy widow for 38 years, cheerless at her childrens' weddings and fiercely critical in her private journal of almost everyone around her. Sometimes she was not too popular with other royalties, and Grand Duchess Olga of Russia remembered her father, the Tsar, referring to her as "'that nasty, interfering old woman." To the common man, however, the Queen-Empress loomed large as a dear woman who had steered the empire to a hitherto unimaginable size - throughout the whole of which her jubilee would be celebrated in a myriad ways. Statues were erected, street parties held, tea parties, balls and civic events were organised throughout the empire, songs and poems composed for the occasion, and of course a whole industry of Diamond Jubilee souvenir item manufacture sprang up. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

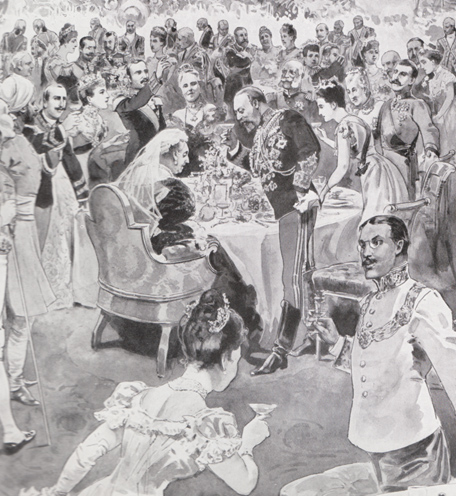

Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee Dinner Party at Buckingham Palace, 21 June 1897:

"The Prince of Wales Proposing the Toast of Her Majesty's Health"

(Detail of drawing by T. Walter Wilson, in Sir Richard Holmes, Edward VII: His Life and Times, London, 1911, p 411)

|

| |

In order to commemorate the Duchess of Devonshire's much anticipated costume ball, the London photographic firm of Lafayette, who had ten years previously been awarded a Royal Warrant, was invited to set up a tent in the garden behind the house to photograph the guests in costume during the Ball. This would have been a formidable commission for James Stack Lauder, the owner of the firm, and evidence from the extant negatives shows that he had transported from the Bond Street studio a variety of backdrops and props and, of course, photographic equipment.

Lafayette's remit was to photograph guests who would be in costumes ranging from mythological and ancient Greek down to renaissance and oriental characters, and in order to capture the sense of event and location, the studio prepared a new backdrop (a painted canvas stretched on a wooden frame) which represented the lawn and gardens of Devonshire House complete with statuary. In the event of guests desiring a different background, the studio also transported its baronial hall and country estate backdrops as well as some studio balustrade, a piece of wall and a Turkish carpet.

More than 700 invitations to the Ball were sent out a month before the event - although reports of the event stated numbers up to 3,000 - which led to a rush of aristocratic women studying portraits and engravings of ladies "robed for coronation or beheading" in London museums and in turn there ensued an almighty battle to gain the time of the best dressmakers, wigmakers, theatrical costumiers and even metalworkers in London and Paris.

Even though the concept of a career, and particularly a career on stage, was anathema to the British upper classes, it had long been acceptable for woman specifically to perform (usually singing) in front of a select audience provided the event was for charity. Princess Daisy of Pless in particular was renowned for her fine voice. Additionally, dressing up in historical costume to present a tableau vivant was a popular and respectable amusement and means of shedding some of the period's cast-iron inhibitions - even at the sullen court of Queen Victoria. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The suite of rooms inside Devonshire House which was emptied of its furniture for the Ball. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Those invited to the Ball spent fortunes on their costumes which in almost all cases were worn only for this event. The couturier Jean Worth of Paris wrote of "a number of freak orders taken" by his establishment, for which each pearl and diamond was sewn on by hand. One piece of jewelled embroidery kept several girls busy for almost a month, and he claimed that the most expensive costume cost 5,000 francs.

The Duchess of Devonshire instructed her guests to dress around the theme of certain courts, both mythical and temporal. They were to form various processions and perform a quadrille - for which many people practised for weeks. While some guests took their instructions literally, others modelled themselves upon paintings, and thus fell into more amorphous costume groupings, such as "17th century" or "Venetians."

Guests at the Ball fell into two distinct groups, obliged to ignore each others' shortcomings for the sake of form. The majority of the aristocracy were rigidly respectable and conservative in outlook whereas the behaviour of the circle around the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) was so "fast" that Queen Victoria wished to have nothing to do with "Society". Memoirs of the time reveal the frenetic bedroom-swapping activities that took place in the great country houses where a gentleman was expected to be back in his own bed by 4:30 a.m. - just before the servants set about their first daily duties.

As the royal residences were too hallowed for this sort of activity, Edward spent much of his time progressing around the country and visiting the stately homes and palaces of his friends where, as part of the entertainments, a good day's game shooting was proved to have an aphrodisiac effect on both the men and women. Among the images seen here, Daisy of Warwick, Daisy of Pless and Mrs James are known to have been intimate with the Prince of Wales, whose wife, Alexandra, turned a blind eye and a deaf ear to his wanderings and absorbed herself with her children who almost worshipped her.

There is no accounting as to why only certain guests were photographed during the Ball, but it can be assumed that, due to the complexity of their costumes and the exposure times needed for the glass plate negatives, there simply was not enough time to capture all the guests. In a newspaper interview the following years, James Lafayette claimed to have photographed 200 sitters in four and a half hours – a staggering speed of 1 minute 21 seconds per photograph! Additionally, perhaps not all the male guests were keen to be memorialised looking like a “tomfool” – as the Hon Reginald Baliol Brett (later 2nd Viscount Esher) complained in his diary!

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

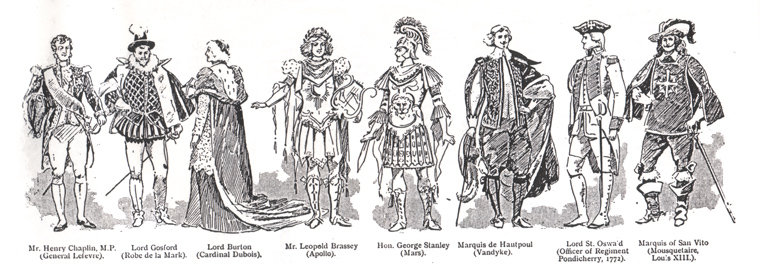

A line drawing of a group of male guests in costume at the Ball

The Graphic, 10 July 1897 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The knowledge that an album would be published with portraits of the guests in costume may well have led those who were not satisfied with the results of the hurried photographic session at the Ball to visit the Lafayette studio once or twice more with their costumes - some people up to six months after the event. The record of the event was finally published privately in 1899 and contains images made by various leading photography studios. The Lafayette archive at the V&A contains the only known surviving negatives by any photographer from the occasion. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Although almost no original prints from the Devonshire House Ball have been found, it is obvious from a studio contact sheet that this popular series of royals in fancy dress was available for order by the public |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

There was huge press excitement surrounding the Ball, and crowds thronged Piccadilly on the night to watch the illustrious and heavily bejewelled and fantastically-costumed guests arriving in their carriages. From the enormous amount written in newspapers following the Ball and the fact that different publications describe costumes in some cases in identical wording, it is obvious that many of the guests or their costumiers made available detailed costume descriptions in order that they could be reported correctly and with all their pertinent details. In their eagerness to report on the Ball, many newspapers, in their next day's edition, also carried line drawings of the guests in costume and images from the ball would be published over the coming months in a variety of illustrated magazines. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Mrs Arhur Paget as photographed by Lafayette in everyday costume

and as Cleopatra for the Devonshire House Ball |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Lady Wolverton as photographed by Lafayette in everyday costume

and as Brittania for the Devonshire House Ball |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The commission from the Duchess of Devonshire to photograph the Ball would have brought enormous publicity value to the firm of Lafayette who opened their first London studio in 1897 to capitalise on the capital's commercial bulge during the jubilee year. Indeed, contact sheets found in display albums from the London studio show that the firm's regular customers could order prints of the Ball's guests in costume. Only some very few original prints from the Ball are known to exist. In 1924, almost three hundred years after it was built, Devonshire House was demolished to make way for an office block, whose ground floor is now occupied by Marks & Spencer and the Green Park Tube station. Only the magnificent wrought iron gates of the house survived complete with their sphinx-topped Greek revival piers, relocated to the edge of Green Park on the opposite side of Piccadilly where they can still be seen. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Devonshire House, Piccadilly, 2003, now an office building with a branch of Marks & Spencer and a tube entrance at ground floor level

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|